Hydrogen, the universe’s most abundant element, holds significant promise as a clean energy carrier. Its potential to decarbonize various sectors, from transportation to heavy industry, hinges on efficient methods for its storage and transport. Compression is one such critical process, fundamentally altering hydrogen’s properties and enabling its practical application. This article explores the multifaceted impact of compression on hydrogen, delving into the physical principles, engineering challenges, and energy implications.

The Fundamentals of Hydrogen Compression

Hydrogen’s inherent nature presents unique challenges for compression. Unlike many conventional fuels, hydrogen at atmospheric pressure is a dilute gas with a low energy density by volume. To make it a viable energy source – to fit more of its energetic potential into a manageable space – its density must be increased. Compression achieves this by forcing hydrogen molecules closer together, thereby increasing the number of molecules, and consequently, the energy stored, within a given volume.

Thermodynamics of Compression

The process of compressing a gas is governed by thermodynamic principles. When you compress hydrogen, you are doing work on the gas. This work causes its internal energy to increase, which manifests as a rise in temperature. This phenomenon is known as adiabatic heating. Imagine squeezing a balloon; it gets warmer. Similarly, as hydrogen’s molecules are forced into closer proximity, they collide more frequently and with greater intensity, leading to an increase in temperature.

The relationship between pressure, volume, and temperature during compression is described by gas laws. For an ideal gas, the relationship is often approximated by the ideal gas law ($PV = nRT$), though real gases, like hydrogen, deviate, particularly at high pressures. The adiabatic process, where no heat is exchanged with the surroundings, represents the most energy-intensive scenario. In reality, compression is often closer to an isentropic process, which assumes a reversible adiabatic process. However, real-world compressors are not perfectly reversible, and some energy is lost to friction and heat dissipation, making the process polytropic. Understanding these thermodynamic pathways is crucial for designing efficient compression systems.

Hydrogen’s Properties and Compression

Hydrogen’s low molecular weight and small atomic size contribute to its unique behavior under compression. Its intermolecular forces are weak, meaning it requires significant pressure to achieve densities comparable to liquid fuels. This is a key reason why high-pressure gas storage is a primary method for hydrogen.

Furthermore, hydrogen exhibits deviations from ideal gas behavior at elevated pressures. Factors like van der Waals forces and the volume occupied by the molecules themselves become more significant. These deviations necessitate careful consideration in thermodynamic calculations and compressor design to ensure accurate predictions of pressure, volume, and temperature changes. The ease with which hydrogen can permeate through materials also becomes a factor at high pressures, requiring specialized sealing and containment solutions.

Types of Hydrogen Compressors

The practical realization of hydrogen compression relies on various types of compressors, each with its own advantages and limitations. The choice of compressor depends on the required pressure, flow rate, and efficiency considerations.

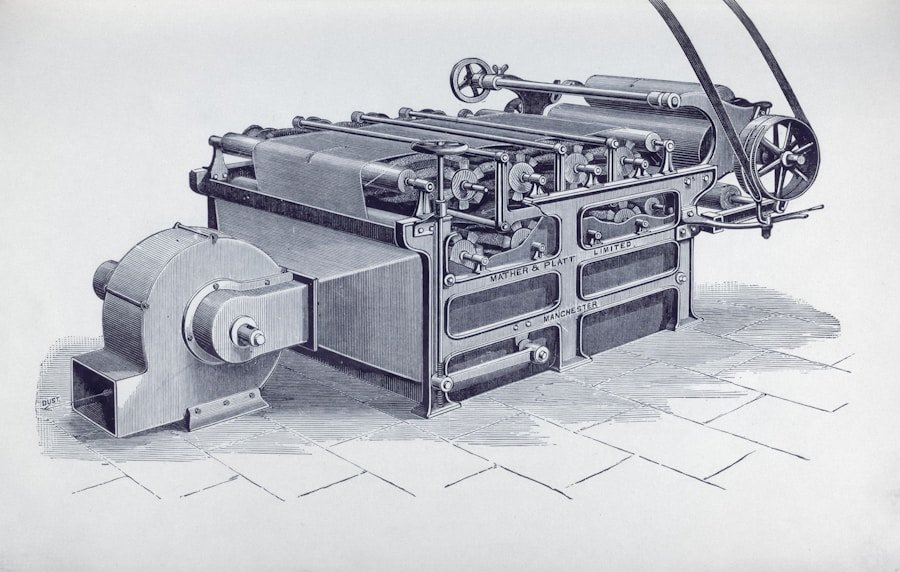

Reciprocating Compressors

Reciprocating compressors, often referred to as piston compressors, are a common choice for hydrogen compression. They operate much like the engine in a car: a piston moves within a cylinder, drawing in hydrogen, compressing it, and then discharging it.

Positive Displacement Mechanism

The core principle of a reciprocating compressor is positive displacement. This means that a fixed volume of hydrogen is trapped and then reduced in size. The compression occurs in stages, with multiple cylinders often used to achieve higher pressures in a more efficient manner. Intercooling between stages is crucial to manage the heat generated, as excessive temperatures can degrade seals and lubricants, and reduce efficiency.

Applications and Limitations

Reciprocating compressors are well-suited for high-pressure applications, making them ideal for refueling stations and hydrogen production facilities. However, they can be less efficient at very high flow rates and can suffer from mechanical wear due to the moving parts. Their periodic nature can also lead to pulsations in the discharge flow, which may require dampening.

Centrifugal Compressors

Centrifugal compressors utilize a rotating impeller to impart kinetic energy to the hydrogen gas, which is then converted into pressure through a diffuser. They are characterized by their continuous flow and high volumetric capacity.

Rotational Energy Conversion

The process begins with the impeller spinning at high speed. As hydrogen flows through the impeller, centrifugal force accelerates it radially outwards. This imparts a high velocity to the gas. The diffuser, a stationary component with diverging passages, then slows down the high-velocity gas, converting its kinetic energy into potential energy in the form of increased pressure.

Suitability for Large-Scale Operations

Centrifugal compressors are often favored for large-scale industrial applications, such as in hydrogen production plants, where high throughput is a primary requirement. They generally offer higher reliability and lower maintenance compared to reciprocating compressors due to fewer moving parts in contact with the gas. However, achieving extremely high pressures with a single-stage centrifugal compressor can be challenging, and multiple stages are often employed.

Other Compressor Technologies

Beyond reciprocating and centrifugal designs, several other technologies are employed or under development for hydrogen compression. These often target specific niches or offer enhanced efficiency.

Ionic Liquid Compressors

This emerging technology utilizes ionic liquids – salts that are molten at relatively low temperatures – as a medium for compression. The hydrogen dissolves into the ionic liquid, and the volume of the liquid is then reduced, effectively compressing the hydrogen. This method offers the potential for lower energy consumption and reduced leakage issues.

Diaphragm Compressors

Diaphragm compressors use a flexible diaphragm to separate the gas from the compression mechanism. This provides a hermetic seal, preventing gas leakage and contamination. They are particularly useful for high-purity hydrogen applications.

Energy Implications of Hydrogen Compression

Compressing hydrogen is an energy-intensive process. The energy required is directly related to the pressure increase and the efficiency of the compressor. This is a significant factor in the overall cost and environmental footprint of hydrogen utilization.

Work of Compression and Isentropic Efficiency

The theoretical minimum energy required to compress a gas is known as the isentropic work of compression. This is the work done in an ideal, reversible adiabatic process. In reality, compressors are not perfectly efficient. The isentropic efficiency of a compressor quantifies how close its performance is to this ideal. A lower efficiency means more energy is lost to friction, heat, and other inefficiencies, resulting in a higher actual work of compression.

The work done is proportional to the pressure ratio (the ratio of discharge pressure to suction pressure) and the amount of gas being compressed. As you squeeze hydrogen to higher pressures, the energy input required increases significantly.

Energy Dissipation and Heat Management

As hydrogen molecules are compressed, their kinetic energy increases, leading to a rise in temperature. This heat must be managed to prevent damage to the compressor and to maintain efficiency. Intercooling between stages in multi-stage compressors helps to lower the gas temperature, reducing the work required in subsequent stages and mitigating thermal stress on components.

The energy lost to heat is essentially wasted energy that cannot be recovered as useful work. Effective heat management strategies, such as efficient intercoolers and proper ventilation, are critical for optimizing compressor performance and reducing operational costs. This heat can be a byproduct of the compression process, and its management often involves heat exchangers that transfer thermal energy to a cooling medium, such as water or air.

Impact on Hydrogen’s Energy Density

Compression dramatically increases the volumetric energy density of hydrogen. While gaseous hydrogen at atmospheric pressure has a very low energy density, compressing it to 700 bar (a common pressure for vehicle refueling) increases its energy density by a factor of over 400. This is a crucial enabler for practical hydrogen storage, allowing vehicles to carry enough hydrogen for a reasonable driving range.

However, it’s important to note that while compression increases volumetric energy density, it does not increase the gravimetric energy density (energy per unit mass). Hydrogen remains one of the lightest elements, and its energy content per kilogram is high regardless of its pressure. The challenge lies in packaging that high gravimetric energy into a usable volume.

Engineering Challenges in Hydrogen Compression

The high pressures and reactive nature of hydrogen present several engineering challenges that must be addressed in the design and operation of compression systems.

Material Selection and Integrity

Hydrogen can embrittle certain metals, making them susceptible to cracking under stress. This phenomenon, known as hydrogen embrittlement, is a significant concern for components operating at high pressures. Specialized alloys and materials that are resistant to hydrogen embrittlement are therefore crucial for compressor construction, pipelines, and storage vessels.

The selection of appropriate seals, gaskets, and valve materials is also critical. These components must maintain their integrity under high pressure and prevent leakage of hydrogen, which is both flammable and can escape through very small openings. Elastomers and composites are often employed, chosen for their compatibility with hydrogen and their ability to withstand the operating conditions.

Sealing and Leakage Prevention

Preventing hydrogen leakage is paramount for safety and efficiency. Hydrogen molecules are small and can easily permeate through many materials that would effectively contain other gases. High-pressure seals often involve multiple layers of sealing materials and sophisticated designs to create a robust barrier.

Regular inspection and maintenance are essential to detect and address any potential leaks early. The risk associated with hydrogen leaks is amplified by its low ignition energy and wide flammability range, meaning it can ignite with a small spark and burn over a broad concentration in air. Therefore, leak detection systems and strict operational protocols are integral to safe hydrogen compression.

Safety Considerations and Risk Mitigation

The inherent flammability of hydrogen necessitates stringent safety measures. Compression systems must be designed with robust safety features, including pressure relief valves, emergency shutdown systems, and containment measures to mitigate the consequences of any potential incident.

The operational environment also plays a role. Areas where hydrogen is compressed and stored need to be well-ventilated to prevent the accumulation of leaked hydrogen. Ignition sources must be strictly controlled, and personnel must be trained in safe handling procedures. Risk assessments are continuously conducted to identify and address potential hazards throughout the entire hydrogen value chain.

The Broader Impact of Compression on Hydrogen’s Role

| Compression Ratio | Hydrogen Purity | Energy Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| 10:1 | 99.5% | 85% |

| 20:1 | 99.9% | 90% |

| 30:1 | 99.99% | 95% |

The ability to effectively compress hydrogen is not merely a technical detail; it is a fundamental enabler of its widespread adoption as a clean energy solution.

Enabling Hydrogen Infrastructure

Efficient and reliable hydrogen compression is the backbone of hydrogen infrastructure. It allows for the necessary pressures required for vehicle refueling, enabling the practical use of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Without effective compression, the energy density required for automotive applications would be unattainable.

Furthermore, compression is vital for the transport of hydrogen, whether through pipelines or in pressurized vessels. While liquefaction offers higher energy density for long-distance transport, compression remains a more energy-efficient and cost-effective option for many applications, particularly for medium-range transport and local distribution. The development of more efficient and lower-cost compression technologies directly impacts the economic viability of the entire hydrogen ecosystem.

Economic Feasibility and Cost Reduction

The energy consumed during compression represents a significant portion of the cost of hydrogen. Reducing this energy requirement through improved compressor design and operation directly translates to lower overall hydrogen costs. This makes hydrogen more competitive with existing fossil fuels.

Research and development efforts are continuously focused on improving compressor efficiency, reducing wear and tear, and extending lifespan. Innovations such as high-efficiency motor drives, advanced control systems, and optimized aerodynamic designs contribute to these cost reduction goals. As economies of scale are achieved and technologies mature, the cost of hydrogen compression is expected to decline further.

Advancing the Hydrogen Economy

Ultimately, mastering hydrogen compression is a key step in realizing the vision of a hydrogen economy. It unlocks the potential of this clean fuel to decarbonize sectors that are difficult to electrify, such as heavy-duty transport, aviation, and industrial processes.

The progress in compression technology influences the pace at which the hydrogen economy can develop. As compression becomes more efficient, reliable, and affordable, the adoption of hydrogen as a primary energy carrier will accelerate, contributing to global efforts to combat climate change. The journey “from gas to power” for hydrogen is intrinsically linked to its ability to be conveniently and economically compressed, making it a dense, transportable, and usable energy resource.